Free Justin Rodwell: a family’s year-long quest for justice

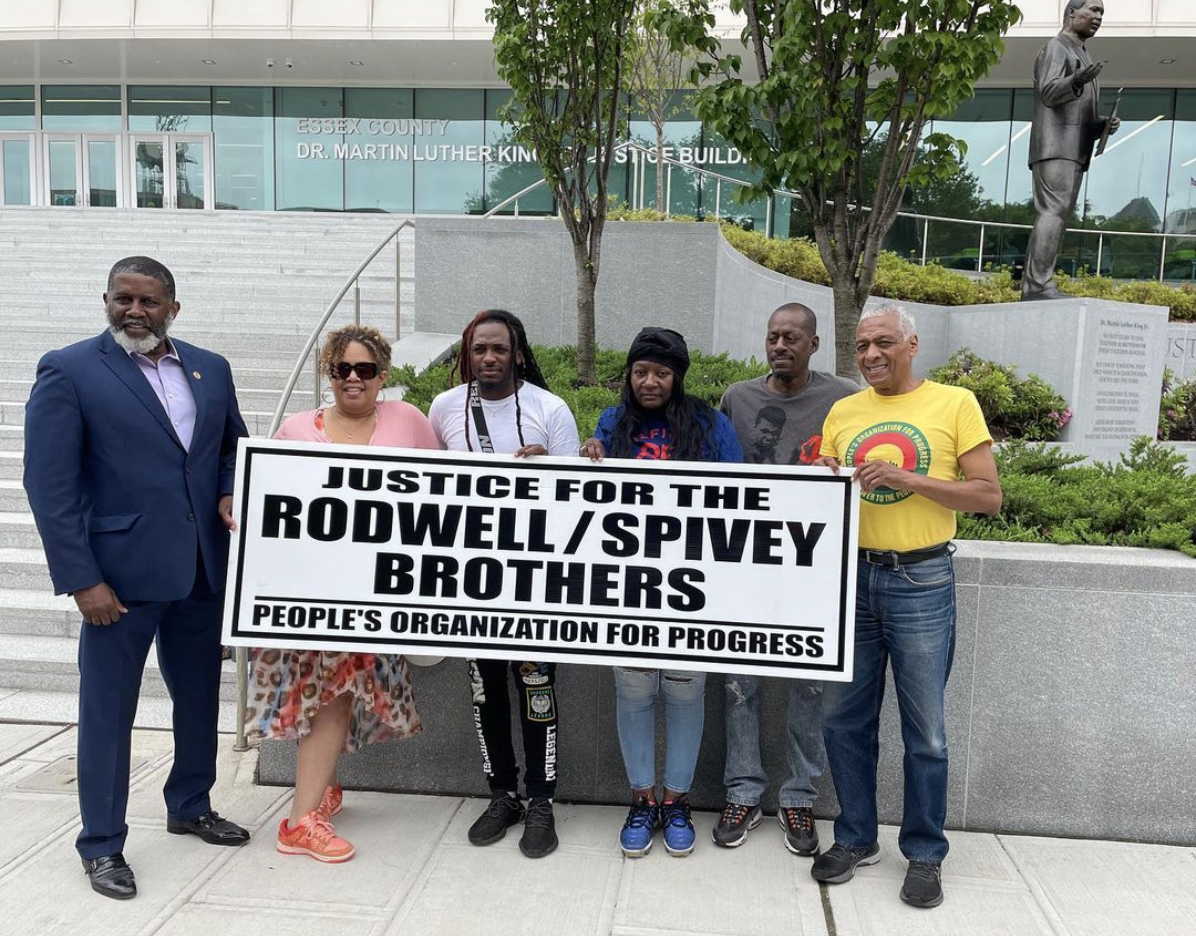

On June 1, Rick Robinson, chairman of the NJ NAACP Criminal Justice Committee, attorney Cynthia Hardaway, Jaykill Rodwell, Monique Rodwell, Robert Tyson and Larry Hamm, chairman of the People's Organization for Progress (POP), stood outside the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Justice complex.

NEWARK, N.J.—It's been a year since Justin Rodwell was detained at Essex County Correctional Facility. Arrested after an incident described in the media as a "mob" attack on police, Rodwell maintains that he acted in self-defense. In the past year, he's missed precious moments with his children: His daughter's first prom and eighth grade graduation, his toddler's first steps. And he is missed by family and friends who continue to call for their loved one's immediate release.

While the court has denied a motion to dismiss the case, the judge's opinion ruled that racial profiling on the part of the arresting officers is a viable defense for trial. Still, advocates hope it does not go that far and say the case should have been dismissed long ago.

The cost of justice, one family's saga

On the afternoon of June 1, 2021, Justin Rodwell and Jaykill Rodwell stood outside of their family home. It was a partly sunny day with temperatures hitting the low 70s as the two shot the breeze on their block—a cul de sac at the intersection of Fabyan Place and Cypress Street in Newark's South Ward.

Later, the brothers were joined by a neighbor in a silver minivan. By their account, it was just another Tuesday, and at around 1:30 p.m., they were looking inside the van to see their friends' selection of clothing. Then all of a sudden, they were approached by men who drove up in an unmarked vehicle.

Police body cam footage captured the scuffle that ensued: Justin was twirling one of his dreads as the men—undercover police officers—confronted them. Two other brothers, Jasper Spivey and Branden Rodwell were nearby and rushed to intervene.

The footage does not have audio all the way through, and the camera falls to the ground a few times. Shouts are heard as the officers pin Jaykill Rodwell to a fence, and his brothers try to stop what appeared to be an attack against Jaykill, who'd been holding a black fanny pack. The plainclothes officers seized the fanny pack at the scene and later asserted that they decided to investigate the men based on suspicion that the bag contained a gun. Yet, no gun was recovered during the incident.

During her first conversation with PSA in late July of 2021, Ms. Rodwell stood outside during a short work break. She paused a few minutes in to take an incoming call from her son Justin at Essex County Correctional Facility. At that point, he'd been detained for nearly two months. She said Justin Rodwell was trying to stay strong and expressed concern for his children.

“My son Justin just had a baby, and he has custody of his daughter. And, he takes care of his children," she said. Ms. Rodwell wanted people to know that the media portrayals of her son are inaccurate: "Yeah, they probably had it rough as they were coming up when they were in school. But they changed their whole lives around. Now they're doing positive things."

Ms. Rodwell says her sons, who are into the music industry, threw parties that brought rival gangs in the neighborhood together. "They were also getting young kids off the street, giving them studio time," she said. They've even deejayed for local events hosted by the Newark police. "So they have been doing good things in the community, helping different people through their music."

In addition to coping with the stress of the incident, and Justin's ongoing detainment, Ms. Rodwell said that police had harassed her family. She said police had followed her and other family members as they walked around the neighborhood. And within days of her sons' arrest, Ms. Rodwell said police came into her home unannounced, with guns drawn, frightening everyone—especially her young nephew and grandson. They eventually showed a search warrant, but she said police traumatized the family, causing her to have an anxiety attack and stepping on her grandson's insulin needles.

PSA reached out to the Newark Police Department for a response but has not yet received comment.

By way of Rodwell's family, PSA obtained a copy of the incident report filed by the Newark Police concerning the events of June 1, 2021. The report states that two detectives, accompanied by a lieutenant officer, were traveling westbound on Cypress Street from Fabyan Place when one of the detectives "observed a male wearing a white shirt and long dreads within the area, which prompted him to stop, exit his vehicle and further investigate."

The stop arguably violates these brothers' fourth amendment rights, which affords protection from "unreasonable searches and seizures" by the government. Advocates say the stop also runs afoul of the Consent Decree—a comprehensive settlement with the City of Newark to compel thorough police reforms and end practices such as unconstitutional stops, searches and use of excessive force, which heavily impact people of color in Newark.

"They were targeted," said Ms. Rodwell, describing what happened to her son as a case of racial profiling or the use of race or ethnicity as a reason for suspecting someone of having committed an offense. "They were Black men standing there, and they decided to get out and attack them. And it's not right. So we need justice."

Ms. Rodwell talks to her son Justin about four times a week. She's concerned for his safety at Essex County Correctional facility, where one detainee died this past May. The death marks the fourth at the jail in recent months. Back at home, the ordeal has also levied a financial burden on the family, says Ms. Rodwell, who's thankful that she still has her job.

"We feel that the gentleman has been wrongfully arrested, and there's racial profiling involved," said Rick Robinson, chairman of the NJ NAACP State Conference and the Newark, NJ NAACP for Criminal Justice matters. "This is also a situation where the Newark Police Department did not do their due diligence and involve their presence to try to work with these people."

"The fight this family has put up has been tremendous, and it costs an excessive amount of money," said Robinson. "Because Justin Rodwell is locked up, he's unable to work. He's not able to obtain an income to take care of his children, and he's not able to do something for his mother."

Her sons have not been able to find gainful employment in the past year, as coverage of the June 2021 incident has shown up in background checks.

Ms. Rodwell has trouble sleeping and has health complications that make it difficult for her to keep showing up to every rally and press conference, but she soldiers on for her son. The community has also supported the family: neighbors call on Mrs. Rodwell, help her pass out leaflets about the case in the neighborhood, and collect money to send to Justin so he can buy food.

Detainees and their families face steep prices for commissary purchases of basic supplies such as food and hygiene products. A 2018 survey conducted by the non-profit Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) found that, on average, commissary sales per person amounted to $947 per year. PPI’s report examined data from Illinois, Massachusetts and Washington state based on the rare availability of commissary data and this sampling’s representation of a cross-section of different prison systems nationwide.

The researchers also found that while incarcerated workers earned $180 to $600 per year, the cost of basic necessities at jail and prison commissaries far outpaced any meager earnings.

“Every day, he’s calling me, asking me for money,” said Ms. Rodwell at a press conference in June. “At times, I got bills. I can’t afford to put money on your books until you can eat. But I gotta go through this because the system f— up, excuse my language, they screwed me. So now I have to go into what I have saved.”

“I work hard every day to support my son a whole year while he’s in [there], and all my money is gone now,” she continued. “You know, it’s crazy because they jumped out and racially profiled my family. And it just makes no sense.”

The Newark Police Division’s (NPD) transparency data, available to the public, shows that in 2019 officers disproportionately targeted Black individuals for searches during stops. The highest reported figure was during August 2019, with 723 such stops.

A graph from the Newark Police Division (NPD) shows that Newark police officers disproportionately targeted Black individuals for searches during stops compared to white and Hispanic individuals in 2019.

At a rally held by the People's Organization for Progress (POP) earlier this month, supporters marched from the Dr. Martin Luthier King Jr. Justice Complex to Essex County Correctional on Dorms Avenue. Once more, the marchers chanted for Justin's release.

"Why is he still there? Everybody is asking the same question," said Ms. Rodwell. "For third and fourth-degree charges? Release him!"

Due to scheduling conflicts, the court pushed a trial date initially scheduled for Thursday, June 9, to July 12. The delay has meant another month-long stretch before Mr. Rodwell learns of his fate.

New Jersey v. Justin Rodwell and the case for racial profiling claims

In September of 2021, an Essex County grand jury returned an eight-count indictment against brothers Justin Rodwell, Branden Rodwell, Jaykill Rodwell and Jasper Spivey for charges of 3rd-degree aggravated assault, 4th-degree obstruction of the administration of the law and 3rd-degree resisting arrest. The degrees indicate all are lesser, though indictable charges in the state of New Jersey.

All four brothers have separate counsel and had a detention hearing after the arrests, but three were released and allowed to go home while waiting to be called back to court. In Justin Rodwell's case, the court ruled that he remain in detention at Essex County Correctional facility.

"Previously, everyone got bail, and if you could afford to pay it, you'd bail out. If not, you'd stay in jail. You could also ask the judge to reduce your bail. But the new bail reform gives the judge the authority to detain a defendant or release them," said Rodwell's attorney, Cynthia Hardaway, referring to the Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Act of 2017. The measure enacted a constitutional amendment and significantly changed how defendants are processed in the New Jersey Courts.

Bail reform allowed for the "pretrial detention of certain criminal defendants" and ended the use of cash bail as a condition of a detained person's release, which could unfairly burden the poor. Instead, the new law enforces a risk-based system. And so judges consider the recommendation of pretrial services, which is based on information gathered about newly arrested defendants, such as a person's age, flight risk or pending charges, to rule in favor of or against release.

The New Jersey Judiciary has reported a stark decline in the number of people who remain in jail because they could not pay a cash bond of $2,500 since the reforms. The difference of 14 such instances in 2020 compared to some 1,500 in 2012 indicates the reforms' success. Still, critics say cases like Justin Rodwell’s show their limitations.

"The judge opted to detain him, even though the pretrial service's recommendation was release. And even though he only has lesser third and fourth-degree charges," said Hardaway. The judge's stated reason for detaining Rodwell was that Justin might obstruct the criminal justice process if released—a decision his counsel appealed to the appellate division and the New Jersey Supreme Court.

Hardaway has been trying to find a material change of circumstances—such as new evidence that weakens the state's case—to justify filing a motion to reopen the detention hearing.

"But that's difficult because the change would have to do with the evidence and not the client's personal circumstances, and it's very rare to meet that standard. Moreover, filing a motion to reopen the detention hearing stops the speedy trial clock," said Hardaway, referring to a detained person's right to a trial within six months of their indictment under recent criminal justice reforms. So the more motions an attorney files on behalf of a client, the longer the case draws out.

"If they can work out some type of plea that's satisfactory to everyone, the case could plead out, or the next step is to go to trial," Hardaway continued. "But I hope this opinion leads to some movement from the prosecutor's office that would resolve this case and let these young men go ahead with their lives."

In March, Hardaway filed to dismiss the indictment, citing factors including prosecutorial abuse and racial profiling. The state filed a brief in opposition. And in April, New Jersey Superior Court judge, Hon. Michael L. Ravin heard oral arguments on the motion to dismiss the case, which he subsequently denied on May 16.

The judge states that the court found no prior cases to support Justin's application for dismissal. But the judge did find that Rodwell's claims of racial profiling and violation of civil rights would have standing at trial and in civil court:

Should Defendant want to argue that the officers racially profiled him and his codefendants, performed an illegal stop, and that he and his codefendants were acting in self-defense, that can be argued at trial. Should Defendant want to argue that he is not guilty of the offenses for which he is charged because the officers were not acting under the color of their official authority, or because the officers were not exhibiting evidence of their authority, he may argue that at trial. Should Defendant seek relief for the officers' or prosecutor's alleged violation of his civil rights, he may proceed in civil court. The Court would note that Defendant may also have recourse under N.J.S.A. 22C:30-6, which makes it a crime for a public servant to subject individuals to unlawful arrest or detention based on racial profiling.

"He gave validity to our racial profiling claim," said Hardaway. "And that's huge… not just for our case, but for future reference."

Prosecutors, however, say that there is no basis for such an argument. “At this juncture, there is no evidence to support the claim that this defendant was the target of racial profiling,” wrote Katherine Carter, a spokesperson for the Essex County Prosecutor's Office, in a statement. “We advocated for detention of this defendant based on the facts of the case. A Superior Court Judge accepted our argument. The Appellate Division affirmed the judge's ruling.”

“This defendant was indicted by a grand jury, and we are ready to go to trial,” she continued. “However, the trial has been delayed because the defense has filed a motion to suppress evidence. We expect the defendant will remain in custody until trial unless a judge rules otherwise.”

After a year-long struggle, Rodwell, his family and supporters are hopeful for a just outcome. And they continue to make their case in the court of law, and of public opinion.

Correction: A previous version of this article’s thumbnail said those pictured in the thumbnail stood in front of the Essex County Correctional Facility. They were in front of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Justice complex. It was corrected.