Yes, there Was Black Activism in the 1800s

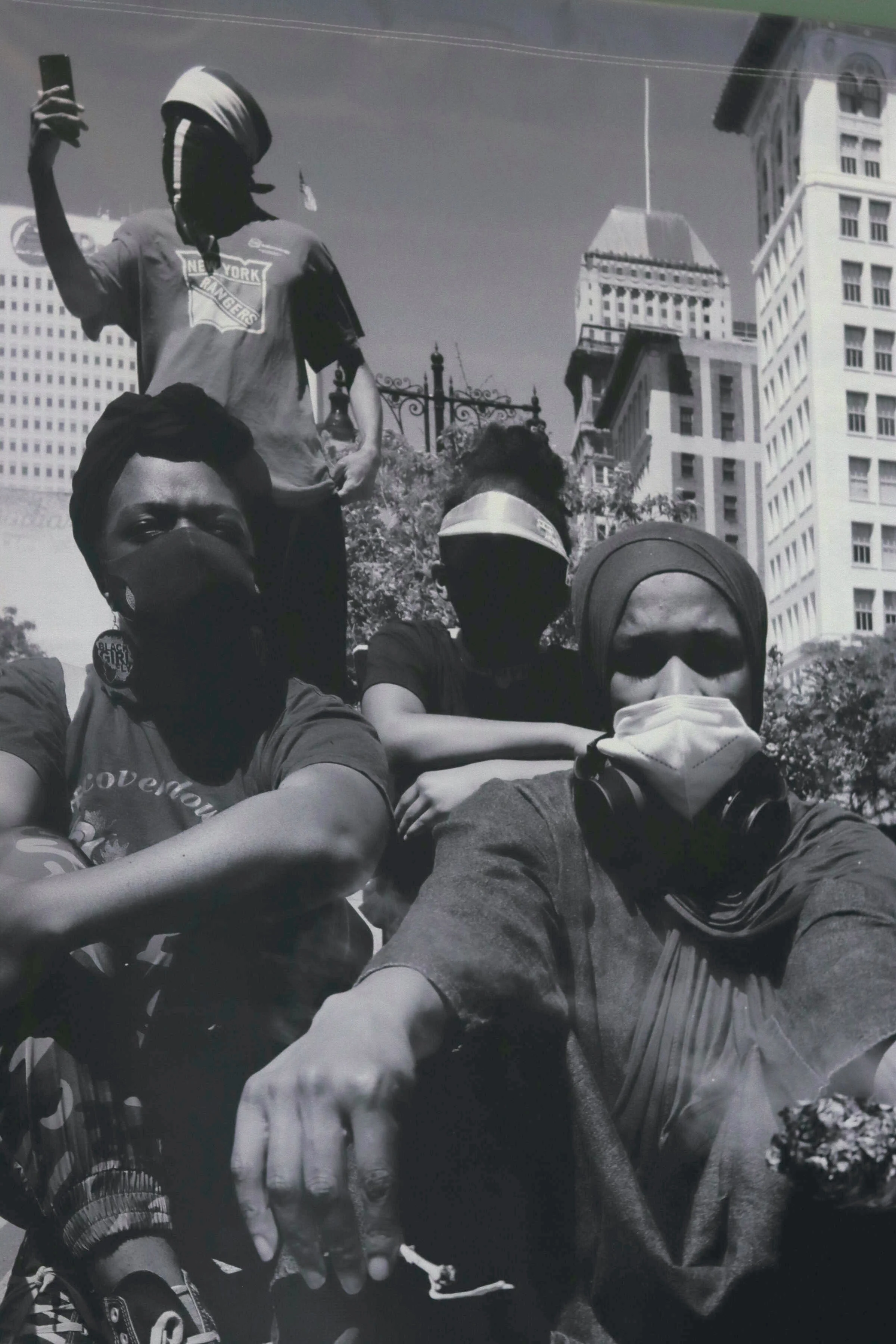

NEWARK, NJ—Curator and historian Noelle Lorraine Williams seeks to educate and remind Newark residents of their history—one filled with striving and rebellion. Her recent exhibition, Black Power! 19th Century, on display at the Newark Public Library from July 9 through Sept.1, revisits Black activism in Newark. In an interview with Public Square, Williams discussed the exhibit and her plans to reach others beyond Newark through her art and research.

What is the focus of the Black Power! 19th Century exhibit?

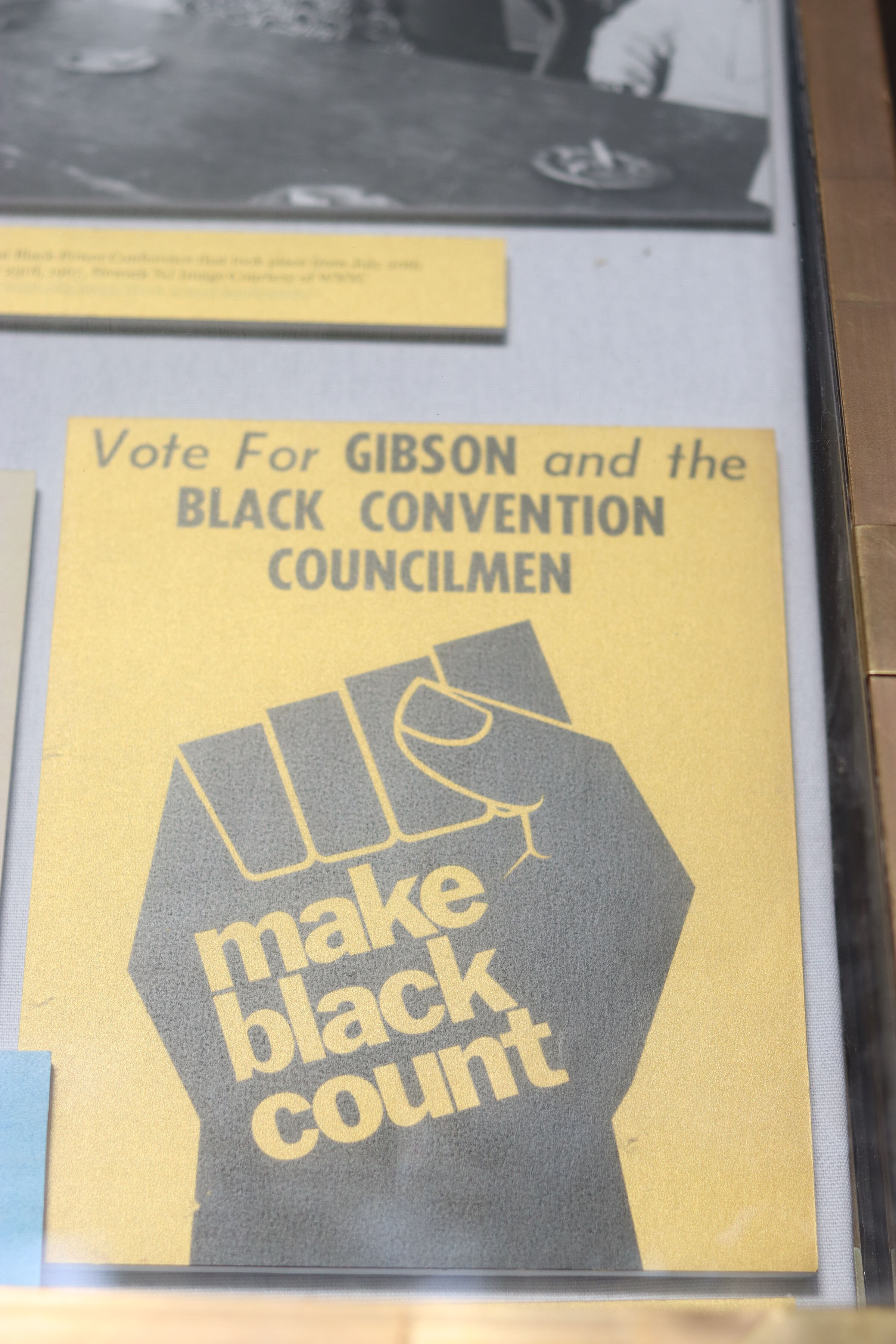

This exhibition is looking at Black activism in Newark in the 1800s. Often we think of the 1960s, most likely the Newark Rebellion, which happened in 1967. Even this year, the Sopranos prequel film, The Many Saints of Newark, is centered within [those uprisings]. So, what was exciting about this project is that I had the opportunity to not only situate Black activism in the 1960s but to show folks there is Black activism in the 1830s and the 1860s.

This exhibit is about Black activists, but you made it a point to include white abolitionists and Native Americans. Can you tell us why this was important?

I was happy to include what I could. I’m demonstrating to people how the term “People of color,” or even “Negro,” in that period encompasses these people who were multi-racial. I’m showing how different people entered the community by default ways or different reasons. The “White Actors in a Black liberation movement”section came about in my research for Radical Women: Fighting for Power and the Vote in New Jersey, [a 2020 Newark Public Library exhibit curated by Williams.] I actually shouldn’t call them all white abolitionists because that’s another thing this research brought for me—they were racist white people who were anti-slavery for economic and religious reasons.

Can you talk about your research and what inspired this work?

So, my undergraduate degree in Social and Historical Inquiry from the New School for Social Research focused on American social justice movements with a specific concentration in African American women's history in the 20th century. My graduate degree is in American Studies with a focus on Public Humanities, and it is from Rutgers University-Newark.

In Newark, we’re just missing public markers around black history, which is funny as a lot of people call Newark a Black city as it’s 50 percent Black. But we don’t have a strong Black history public culture. So, I identified four public spaces to mark, and as I got deeper into the history, I saw there was actually a story.

What do you hope this exhibit will do for its viewers/visitors?

The first thing I want viewers to understand is that the history of African Americans in Newark is long. African Americans have been present here since the 18th century because we have people like Jack Cudjo, an enslaved African who, owned by Benjamin Coe, fought on behalf of Coe for the Revolutionary war. So, we have examples of African Americans who lived in Newark and who were fighting and acting as citizens even though they were deprived of their rights. I want the audience to know the long history of African Americans and African American activism here in Newark. The second is that I want to assist the audience in imagining the period from a Black Activist perspective. We have re-creations of where an enslaved woman was sold on Broad and Market where now people sell goods and music. So, they can say, ‘Oh, where I’m walking here on the street, an enslaved woman was sold.’ [I want] to use art and culture to help illuminate historical truth and facts about Newark. The third is just to show people how different segments of our community’s people have essentially committed to democracy.

Were there concerns/adjustments you had to make for the virtual exhibition?

As a historian, researcher, and curator, I believe in the use of social media and the web—this opportunity for us to reach out to an audience that may not come to academic conferences and galleries to see and engage things. [It] took more time than I anticipated. I jokingly said to a friend of mine that I realized I technically curated three exhibitions with Black Power/19th Century. There’s a certain way you have to present the virtual exhibition that makes sense to the audience. You can only use a certain amount [sic] of images unless you keep creating different ways for people to engage them. The first draft was all on one page for people to scroll through, but it was way too heavy, so I had to break it into subsections.

Historian Noelle Lorraine Williams pictured in 2013 with the Seated Lincoln sculpture near the Essex County Courthouse in Newark, New Jersey. Credit: Colleen Gutwein O'Neal

How did your partnership with the library come about?

The project is actually mine and grew out of the research I did as part of my master’s work at Rutgers University-Newark. Initially, I didn’t necessarily know it would be an exhibition, even though I had an inclination. Whilst I was going through this process and getting lots of positive feedback from my professors, classmates, and others, my advisor, Dr. Mary Rizzo, suggested I partner with the Newark Public Library as a way to bring this information and cultural resources to the public. I definitely believe in partnerships in all of my work. Rutgers-Newark gave me the first little grant to hire a photographer to do the collages, and then the New Jersey Historical Commission provided the project grant for fabrication costs, and I also received a creative catalyst grant from the city of Newark.

What’s your vision for your future exhibitions?

For the next exhibition I’m working on, Blood money, the river, the economy, and the North, I’m approaching it from a more intense multimedia approach. A lot of my framework for my vision for the work I do with public humanities and public history is that it must involve an art and cultural component that’s grounded in historical truth. In that way, it kind of differs from some other fine art practices that will sometimes beautifully imagine something that could’ve happened, whereas, with all the art renderings and cultural work I do, they’re based on real historical actions. The Black Powerexhibition is very dense but written for both audiences that will spend three minutes, as well as those who can spend an hour in it. So, for this third project, I’m going a lot deeper into cultural emergence and creating a portable art piece about slavery in NJ in connection to the economy.

To reach more people, Williams plans to create her upcoming work as traveling art pieces. She's also developing a play on primary sources about black women enslaved and freed in Newark and will have musicians portray these people. She says such works and historical explorations provide an opportunity for viewers to "use their imaginations in understanding that period." For example, she plans to include information about slave trading in Hoboken and the slave ships that docked in Perth Amboy before the Civil War. So as with past exhibitions, Williams will be sharing some more historical truth and information about sites "we may not know, but that influence our trajectory as a state."

"We are honored that Newark Public Library is presenting the important exhibit, Black Power! 19th Century," said Joslyn Bowling Dixon, director of the Newark Public Library. "This is a thoughtful, well-researched overview of the Black artists and activists who laid the foundation for Newark's strong tradition of activism in the 20th and 21st centuries. The events and contemporaneous accounts included in the exhibit provide us with a look at significant local history with national implications."

Beyond Sept. 1 The Black Power! 19th Century: Newark’s First African American Rebellion

virtual exhibit will be available at www.blackpower19thcentury.com.

Historic sites map of the Black Power! 19th Century exhibit featured at The Newark Public Library from July 9 to Sept. 1, 2021. Credit: Noelle Lorraine Williams